“There’s a lot that happened with how Yellowstone was founded. The original park rangers at Yellowstone were the same cavalry that were used to put us on reservations. In fact, Blackfeet people were killed to create Yellowstone Park. And then there was, for decades, for about 100 years, this policy that tried to erase our connection to the land. All the while essentially trying to create this garden of Eden where they would kill all the predator species, raise the species of all the ungulates and bring in people who could get prize hunts [...] We see the same policies to this day in Asia, in Africa, where they’re buying these tracts of land, calling it conservation and arming them with guards and then all these policies follow the conservation model of Yellowstone [...]”,

(Big Wind Carpenter, Northern Arapaho Tribal Member, queer artist, environmental activist, and advocate, living on Wind River Reservation.)

Introduction

Every year, over four million visitors travel to Yellowstone National Park in search of ‘untouched wilderness’. Yellowstone is the world's first national park, established in 1872. Since then, the concept of designating and safeguarding selected areas as national parks has spread around the globe. Yellowstone is the original example of a project that has decisively shaped our understanding of the value of protected nature, the prioritization of national interests over local, often indigenous, relationships with places, and the development of nature tourism. As we can learn from Big Wind’s quote, its creation relied on the systematic erasure of the Indigenous presence from both the protected landscape and its official narrative. This context shaped our approach when we conducted participant observation as tourists in this national park (Leemann 2025).

We were a group of four social anthropologists from Switzerland and an Indigenous activist from Cambodia. The production of wilderness and enduring Indigenous relationships to land sat at the heart of our field research experience in Yellowstone National Park and the Wind River Reservation. Our group participated in collective fieldwork organized by the CUSO Swiss Graduate Program in Anthropology, where 15 doctoral candidates, professors, and Indigenous co-researchers explored conservation practices, Indigenous rights, and tourism dynamics in the world’s oldest national park.

Upon entering the park, we deliberately adopted the perspective of ordinary tourists. The nearly universal reliance on motorized mobility quickly struck us: we did not see any visitors arriving on foot or using alternative transportation at the entrance gates or sightseeing spots. This created an experience that resembled a drive-through, where the landscape is mostly consumed through the car window.

Maintaining the promise of 'pristine nature' requires an elaborate infrastructure of roads, visitor centres, rangers, and carefully managed experiences, which paradoxically depend on intensive human intervention to appear 'natural'.

Thus, tourism constructs wilderness as a spectacle: The park appears pristine, yet is thoroughly mediated by infrastructure, mobility, and consumption.

Reinscribing Indigenous presence

One of our findings from participant observation as tourists exploring the park was that the ties Indigenous peoples had and still have to the area were rarely mentioned to visitors. This absence in the standard visitor experience represents a significant gap in how Yellowstone's history is presented to the public. For over a century, the park's interpretation has largely focused on its geological wonders and natural history while overlooking the profound human connections that span over 11,000 years of continuous Indigenous presence. During our visit to the park, it took three days before we encountered any recognition of Indigenous presence within the park’s narrative.

We further learned that the establishment of the Yellowstone Tribal Heritage Center is a very recent development. Opening for its first season in 2022 to commemorate the park's 150th anniversary, this center represents the first time in Yellowstone's history that Indigenous voices are being directly heard within the park boundaries. We observed how the space functions as a meeting point where Indigenous artists, scholars, and presenters from the 27 associated tribes engage with visitors through both structured programs and informal conversations (Grant 2021; National Park Service 2025).

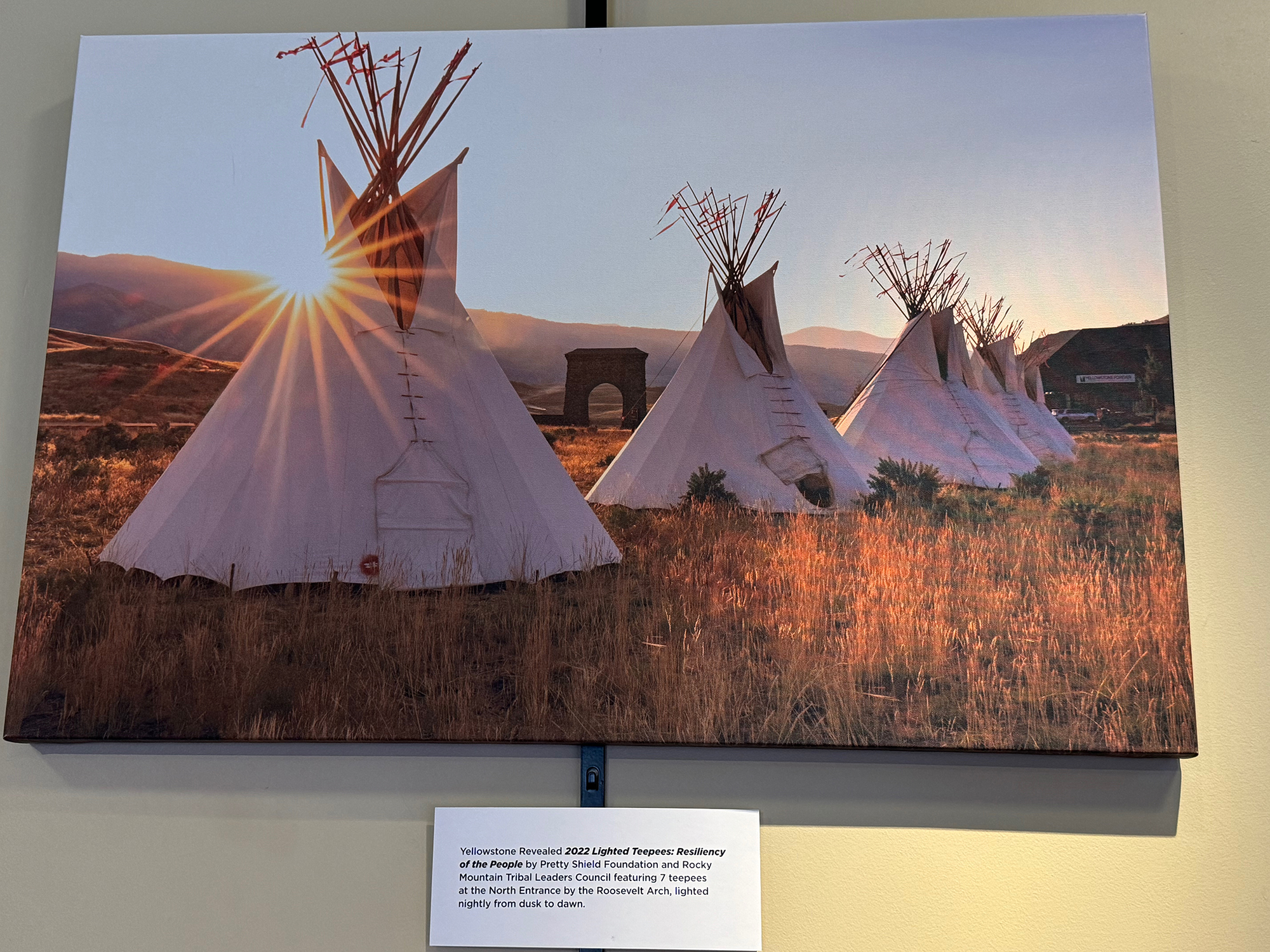

Within this initiative, descendants of Indigenous peoples who frequented the area before their removal in the 1800s have raised an installation of tipis. This practice carries profound symbolic weight, as it represents both a physical and spiritual return to ancestral lands. The tipi installations have taken multiple forms: traditional villages, illuminated ceremonial structures at the Northern Entrance Arch of the park, and contemporary artistic interpretations blending traditional forms with modern Indigenous narratives. These installations serve as more than just educational tools; they are also statements of Indigenous resilience and ongoing connection to the land. They challenge the long-held narrative that Native Americans were merely historical figures who once passed through the region, rather than its original inhabitants and continuing cultural stakeholders.

These contemporary reclaiming initiatives gain particular significance when understood against the broader historical context of displacement and erasure that accompanied Yellowstone's establishment. The creation of Yellowstone fundamentally disrupted human-nature relationships by forcibly removing Native communities from their ancestral homelands. The dominant park narrative has long obscured or minimized Indigenous connections with the land, instead promoting a vision of wilderness as pristine and untouched by human presence.

Yet this narrative of ‘untouched wilderness’ fundamentally misrepresents the reality of the Yellowstone region prior to 1872. Indigenous peoples were integral to shaping and maintaining the landscape long before the area's designation as a national park. The 27 tribes now formally associated with Yellowstone—including the Shoshone, Crow, Blackfeet, Bannock, and Nimiipu—utilized the area seasonally for hunting, gathering, spiritual practices, and sophisticated resource management. Their cultural knowledge and land stewardship practices, including controlled burns, strategic hunting patterns, and selective harvesting, were fundamental components of what European-American settlers would later perceive as "natural" ecosystems.

The Indigenous worldview understands humans as embedded participants within nature rather than external observers or dominators, a perspective that stands in stark contrast to the preservationist philosophy that justified their removal. We learned more from these worldviews during the second part of our field excursion, where we visited the Wind River Reservation, connecting with Indigenous people actively involved in the work of reinscribing and revitalizing their heritage.

For more information, watch the short film about the Wind River Reservation on our website.

Rematriation of the Buffalo

In the Wind River Reservation, we learned about the Wind River Tribal Buffalo Initiative. Since 2016, the initiative has been working to restore the buffalo[1] to ancestral lands as part of broader efforts to reclaim Indigenous sovereignty and heal the land through ecological revitalization. By the late 19th century, the North American buffalo had been hunted to near extinction, a process driven by commercial hunters, expanding settler populations, and government policies aimed at undermining Indigenous livelihoods. The significance of this work becomes clear when understanding the historical rupture that occurred. As Jason Baldes, the initiative's Executive Officer and Eastern Shoshone Tribe Buffalo Manager, explained during our interview: "We come from the Buffalo People, but that relationship was severed. After 1885, we no longer had access to that animal. [...] Colonial influences about land management are still alive". This severed relationship represents more than the loss of a sacred animal—it was the disruption of a fundamental cultural and ecological partnership that had sustained Indigenous communities for millennia.

Our interviews with three members of the initiative revealed how the people of the Wind River Reservation have long maintained a strong relationship with the buffalo, relying on them for sustenance, ceremonies, and the preservation of cultural values, as well as for maintaining the ecosystem. Jason's words underscore how the buffalo restoration is simultaneously an act of cultural reclamation and ecological healing. Since the reintroduction of the bison, there has been a significant positive impact on plant biodiversity (Baldes 2016).

Our fieldwork in both Yellowstone National Park and the Wind River Reservation revealed a fundamental insight that challenges dominant conservation narratives: True understanding of nature requires recognizing Indigenous peoples as active participants in the landscape’s past and present, whose knowledge and stewardship continue to shape meaningful relationships with the environment. Yellowstone’s history is not only a story of spectacular natural wonders but also of human resilience and ongoing efforts to reclaim Indigenous identities within these iconic spaces.

A multimodal website

During our field excursion, we employed ethnographic multimodal methods, integrating photography, video documentation, sound recordings, and written field notes. We brought together these diverse materials, presenting our findings through a multimodal website that seeks to expand anthropological storytelling and highlight the complexities and contradictions inherent in places shaped by colonial histories and ongoing struggles over land, identity, and meaning.

The website’s design presents research as an explorative journey. Just as the visitors of Yellowstone National Park discover ‘nature’ by driving along designated roads, the users of the website browse the interactive map by moving a red car (the mouse). Although the researchers’ journey was linear, visitors of the website are free to discover films, photos, texts, and audios outside of a temporal chronology. They can playfully browse the journey by moving a red car/mouse across an interactive map and navigate content at their own pace. By clicking on illustrations, users reveal what was explored through an anthropological lens, presented in a variety of multimodal formats. Users are not expected to absorb every detail but are encouraged to playfully engage with different outputs as they wish.

The goal of the website is to ignite curiosity, inspiring users to assume the role of an anthropologist, actively engaging with the multimodal content through an immersive experience.

Explore the website here!

Bibliography

Baldes, Jason. 2016. “Cultural plant biodiversity in relict wallow-like depressions on the Wind River Indian Reservation, Wyoming, & tribal bison restoration and policy” Jason Baldes https://scholarworks.montana.edu/items/4afbb578-1b4c-4f9b-bd74-698e524ec35a

Leeman, Esther. 2025. The Original of National Parks. A Tourist Experience. Visual essay. CUSO, 2025. https://anthropology.cuso.ch/yellowstone/05-the-grand-canyon-of-yellowstone

von Dach, Michelle. 2025. The Wind River Reservation. Short film. CUSO, 2025. https://vimeo.com/1090570205/b394041894

Grant, Richard. "The Lost History of Yellowstone." Smithsonian Magazine, January–February 2021. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/lost-history-yellowstone-180976518/

National Park Service. Yellowstone Tribal Heritage Center. U.S. Department of the Interior. Last modified April 9, 2025. https://www.nps.gov/places/000/yellowstone-tribal-heritage-center.htm

National Park Service. 2025. Historic Tribes – Yellowstone National Park. U.S. Department of the Interior. Last modified April 18, 2025. https://www.nps.gov/yell/learn/historyculture/historic-tribes.htm

[1] The terms “buffalo” and “bison” refer to the same species, but their usage slightly differs. Bison is the standard zoological term, a scientific Western designation. In the Wind River Reservation, indigenous peoples, including the Eastern Shoshone and Northern Arapaho, have long referred to the animal as buffalo. Using “buffalo” in indigenous contexts re-centres cultural knowledge, sovereignty, and spiritual connections.