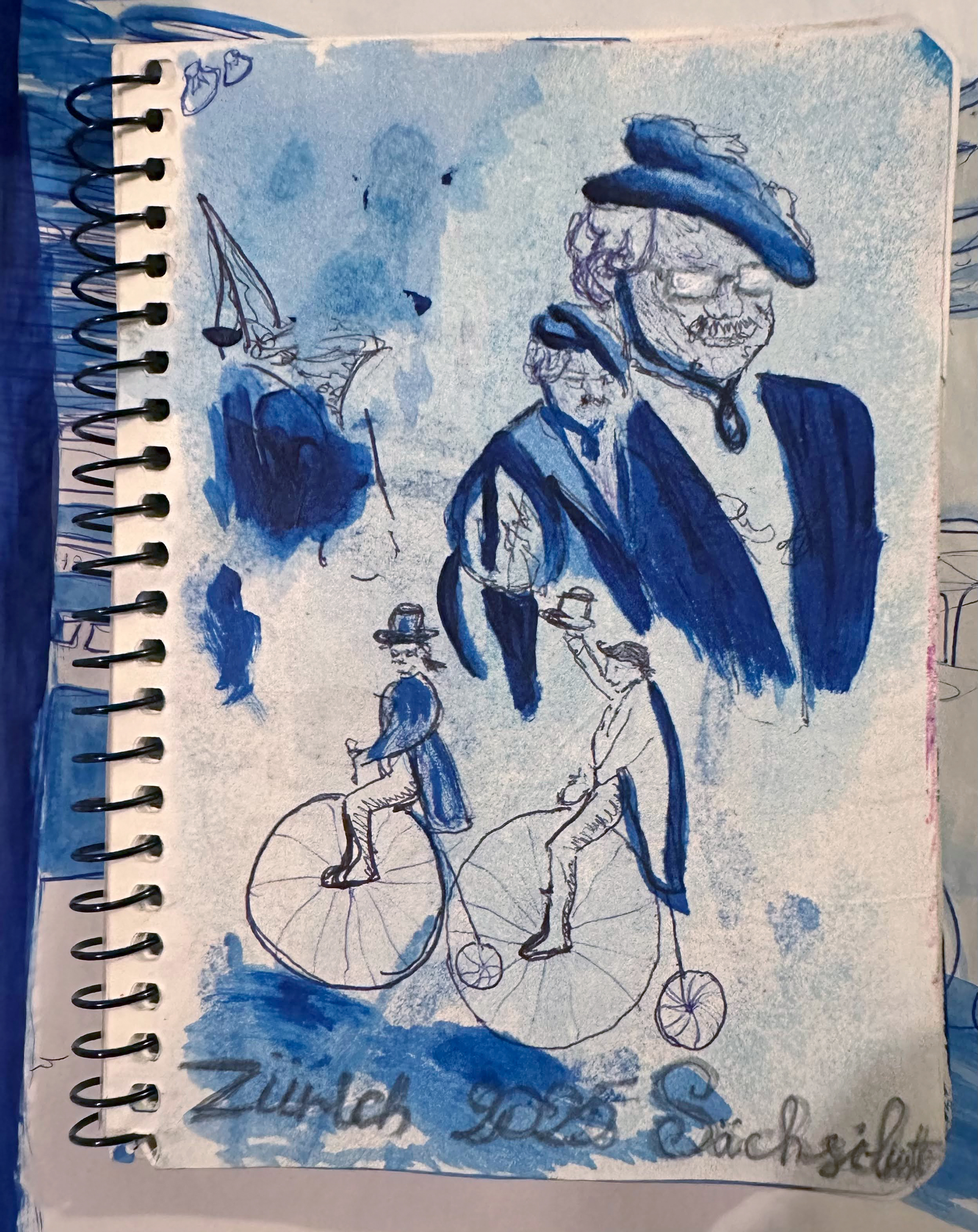

When I first heard the Sechseläuten, it was not the festival itself but the sound of horses, a slow clip-clop on the pavement drifting up to my window. Below, four men in what appeared to be traditional attire walked beside a carriage. Seeing them walking against modern gray buildings quickly reminded me that I had already heard about Sechseläuten. I remembered that other international students suggested me to use this time to extend holidays and travel outside the city, since Sechseläuten "is just one more festival." Despite initial detachment and the unseasonably chilly morning, armed with a long coat and a cool colored sketchbook, I decided to join the festival. My attempts to understand the event through direct questioning had yielded fragmented and often cryptic responses from locals: "We will burn the snowman," "Guilds will be there, you must see it," or "You have to be there! It's not that we are superstitious, we will just check if summer will be good or not." From this moment, the seemingly common festival took on a mysterious air, compelling me to immerse myself further.

Upon arriving at Bahnhofstrasse, I initially perceived the event as a historical carnival, assuming actors were employed by the city to impersonate guilds. But my assumption quickly unraveled when a woman in front of me stood up and rushed towards a horse offering the rider roses. Soon I realized there was too much laughter, too many hugs, kisses, and small talk among them to be actors; they knew one another. In fact, everything was in perfect harmony, baskets of roses at symmetrical distances, chairs lined up perfectly. People were not there just to watch but to participate by giving those beautifully placed roses to guild members. A group of friends near me started to share flowers among themselves debating whom to give them to. This reassured me that I was not attending a passive spectacle where we are expected to just watch and admire, in fact roses painted the web of personal connections. The sheer volume of roses being exchanged was striking. Flowers were everywhere, in hands, on horses, held in baskets, in pockets, on hats and on the ground across the street.

Lost in these floral waves I felt a sense of detachment as I walked through the crowd. This unexpected anonymity gave me the opportunity to observe without pressure, a unique advantage for an impromptu ethnographic inquiry. It felt like moving through a living tableau or being an unseen observer on a stage during theatrical play. As I continued my exploration, it appeared to me that the street was divided into distinct zones, each attracting different groups: standing tourists, families with children and their stroller “parking spaces”, and notably, groups of impeccably dressed senior citizens. Their attire, a harmonious blend of colors, fabrics, and textures, complemented their hairstyles and facial features with striking precision. Closer to the lake, groups were predominantly younger, carrying bags of gifts rather than bouquets. The exchange of gifts was not limited to children, adults also received sweets, alcohol, or baked goods, often without roses in return, suggesting a different symbolic meaning. The act of giving a flower was consistent but mysterious: Why the rose? How do they choose to whom they give it to? I asked myself this question when I noticed how sometimes, even after receiving a gift people would not give a rose in return and overheard discussion regarding saving them for someone they were looking for. Upon spotting a chosen guild member, the excitement of the group in front of me was hard to miss, one of them almost "flying" towards the chosen one for a heartfelt exchange of a rose. This behavior was similar regardless of where I was during the whole day and it was often accompanied by a kiss or a hug. The appearance of small bottles of Jägermeister with colorful ribbons further complicated my understanding of gift giving at Sechseläuten. Later I found a place near two families with children. One individual within this group acted as an informal commentator, identifying passing guild members by name and providing context, often using his phone to look up additional details. Overhearing their conversation reassured me that the participants were not actors but prominent individuals who participated in this event, transforming my perception of Sechseläuten from "just a spring festival" into something far more significant. This unexpected, guided observation provided crucial insights into the festival's social aspects.

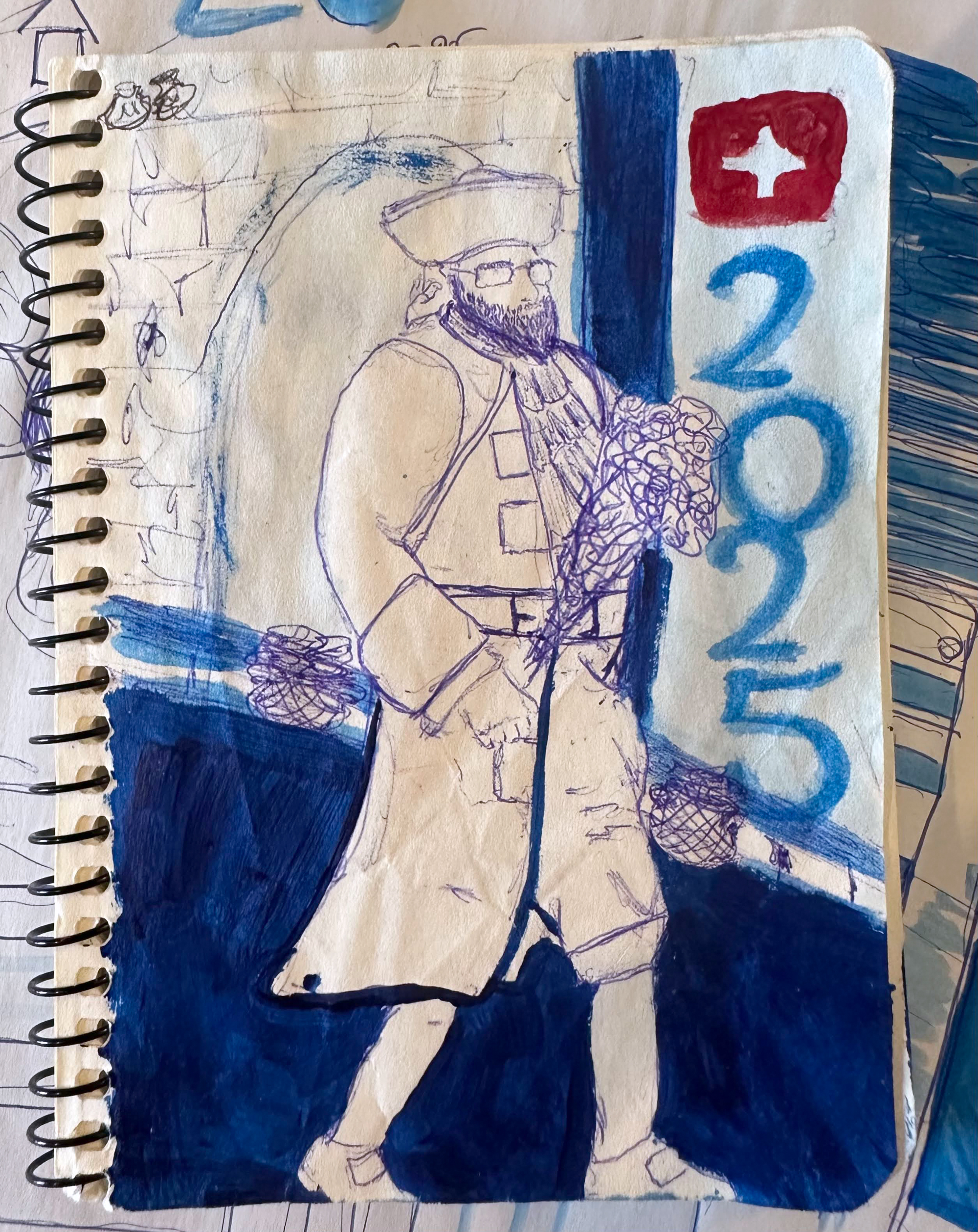

As the temperature rose, I found a place in the shadow next to the building and took off my coat. At that moment my outfit and matching hairstyle suddenly made me “a colorful dot” among a group of tourists. I stood out even more against the gray stones of Zurich’s architecture behind us. This shift seemed to alter my “invisibility”. An elderly woman seated a bit further away from me in a peach silk top and pearls, turned and looked at me for a bit. At this point it was visible that I was also wearing a silk outfit and pearls as well but in a different style. After a moment of mutual recognition, I received my first smile and greeting from the seated guests. The "invisible privilege" I had enjoyed disappeared. From that moment children began waving and approaching me. My increased visibility was soon accompanied by unexpected gifts: an elegant orange rose, a material symbol of inclusion, wine, and then more roses. I knew that giving and withholding these gifts marked the boundaries of community.

At this point I was used to my “role” as an observer; that is why this “shift” made me feel vulnerable at first. If I had previously felt like a guest, now I was puzzled: was I “invited” to participate? I had only just learned what Sechseläuten was, and I was still learning its unspoken rules. With every exchange of smiles, roses or other gifts, I was pushed to participate, which made me feel guilty about accepting the invitations, suspecting that I was included based solely on my appearance. This unintentionally suggested that I belonged. Unexpectedly, my look may have conveyed false belonging, reinforcing my sense of being an impostor. This made me question whether it was even appropriate to accept this “invitation”. Within an hour, it looked as if I had a clear picture of what I was doing. My “masterclass” was successful. Now I knew what to do but did not quite have answers to all my questions. The sense of not having a full picture was not leaving me. The more I mimicked the rituals (smiling, gifting), the more I felt the weight of my ignorance. I experienced that cultural hospitality is an open door, pass through, and you are expected to know the house rules.

Now I know why explanations of what the spring festival was were more puzzling than helping. The ability to understand it depends on one’s cultural fluency. Sechseläuten creates a space where boundaries of time and culture seem to fall for a couple of hours. My journey from observer to participant revealed how easily aesthetic alignment could give an invitation. Zurich’s hospitality, like the festival itself, offered the warmth of inclusion but its secrets are out of reach. I felt how belonging is not just about being seen, it’s about being understood and being able to understand. Sechseläuten is not something you describe, you can only experience, it is a liminal space where the Böögg becomes your reflection. The wind takes not only its ashes but also the burned masks and the performative identities that accumulated over the past year. It does not tell what next summer will look like, it shows you the boundaries of your belonging, making it the most honest and revealing festival I have experienced so far.